An ancient interment site in Russia challenges us to rethink how Paleolithic humans in Europe treated their dead and organized their societies.

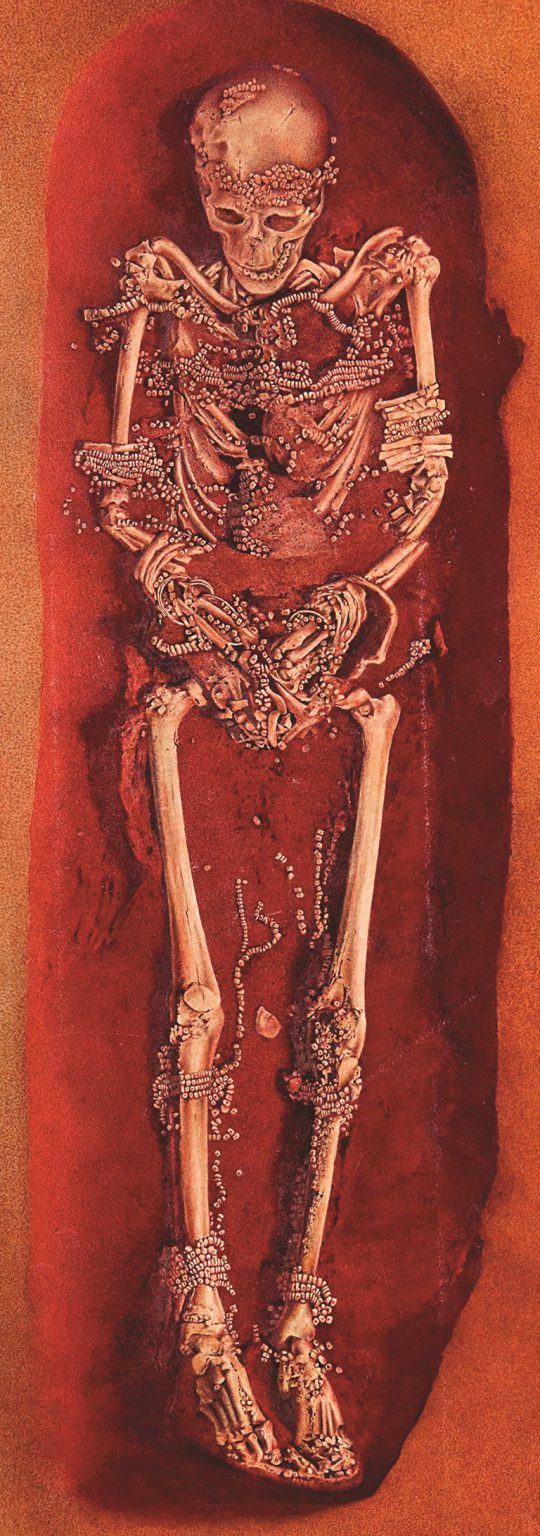

Man in an Upper Paleolithic burial in Sunghir, Russia. The site is approximately 28,000 to 30,000 years old. Discovered in the 1960s. The man was found placed on his back, covered with 3000 mammoth ivory beads, 12 pierced fox canines and 25 mammoth ivory arm bands, with his whole body covered in red ochre

An ancient burial site in Russia is prompting a reevaluation of how Paleolithic humans in Europe treated their dead and organized their societies.

Around 34,000 years ago, hunter-gatherers who roamed the Russian plains began burying their dead at the Sunghir site, located about 200 kilometers east of present-day Moscow.

Sunghir, now regarded as one of the most iconic Upper Paleolithic sites in Europe, was first discovered in 1955 during quarrying operations. Excavations from 1957 to 1977 revealed remains dating back 30,000 to 34,000 years, continuously captivating archaeologists. The site features highly elaborate burials, including that of an adult male adorned with beads and ochre (a red clay earth pigment) and the head-to-head burials of a juvenile and an adolescent, approximately 10 and 12 years old. “Sunghir is the earliest example we have in Europe of very elaborate Homo sapiens burials,” says Natasha Reynolds, an archaeologist at the University of Bordeaux in France specializing in the European Upper Paleolithic. “It is the first point in time where we see these complex mortuary behaviors reflected in the European archaeological record.”

Investigating the complexity and the various ways these ancient people treated their dead at Sunghir could provide new insights into the intricate social world of some of the first Homo sapiens in Europe.

Over the past 60 years, the remains of at least 10 individuals have been discovered at Sunghir, although some bones have been lost over time.

In a recent study published in the journal Antiquity, researchers compiled all available data on the remains at Sunghir. The team presented the most comprehensive description to date of the humans interred and the objects recovered at the site.

The adult male adorned with beads and ochre was between 35 and 45 years old at the time of his death. Bioarchaeological analysis suggests he might have died suddenly, possibly due to a neck wound. His grave, containing about 3,000 mammoth ivory beads, pierced fox canines, and ivory armbands, is remarkable, but the burial of the juvenile and the adolescent is even more so. Along with beads and ochre, the burial included meticulously crafted mammoth ivory spears, ivory disks, and pierced cervid antlers.

However, these extravagant burials are only part of what makes Sunghir stand out in the archaeological record. Research now indicates that the site exhibits a much greater diversity of mortuary behaviors than previously thought.

An adult femur shaft was found in the grave with the two youngsters, while another femur bone was discovered isolated near the graves, suggesting that the body had been left on the surface without formal treatment. A cranium, the first human bone discovered at the site in 1964, was found with artifacts just above the adult’s lavish grave. Although this cranium represents only part of a skeleton, it appears to have been placed there as part of a funerary ritual.

These analyses have led researchers to conclude that at least three different forms of burials were practiced at Sunghir. “What’s impressive here is that diverse mortuary behaviors we see across Europe at this time all come together at Sunghir,” says lead author Erik Trinkaus from Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri.

Radiocarbon dating indicates that these different burials occurred around the same period. Early in the Upper Paleolithic, these ancient people embraced a range of mortuary behaviors within a limited time span. This finding challenges us to recognize that these modern humans may have had rich beliefs about death and how the deceased should be treated.

The contrast between lavish burials and isolated skeletal elements at the site also suggests differentiation among individuals during their lifetimes, reflected in their burial treatments. Although it is unclear what determined the social structure of these people, the evidence at Sunghir suggests that individuals did not necessarily earn their status through their actions. Something else might have determined their position within their communities and how they were treated in death.

The double burial is particularly telling. The spears would have taken considerable time to produce and had high utilitarian value. It is unlikely that these young individuals accumulated enough status in their lifetimes to be buried with such valuable objects.

Sunghir may thus be considered the earliest modern human burial site in Europe with evidence of a social structure not solely based on acquired status. Both the juvenile and the adolescent exhibited physical abnormalities. Although no diagnosis has been established, their disabilities were likely visible to others, which may have contributed to their extravagant burials.

The association between pathological traits and unique mortuary rituals during the Upper Paleolithic is not new. For over a decade, archaeologists have found growing evidence of this connection across Europe, suggesting that such individuals held a unique position. “These elaborate burials should not be seen as the standard way people were putting their loved ones to rest—they are odd,” says Paul Pettitt, a professor of Paleolithic archaeology at Durham University in the U.K. The ornate interments might be seen as ritual acts practiced on rare occasions for individuals who stood out due to their appearance, behavior, or manner of death.

The efforts to bestow distinction in death and the variety of burial treatments are “powerful testaments to the complexity and humanity of our ancestors,” says Reynolds. “It suggests something really complex is going on in terms of the worldviews of the people who were living there.”