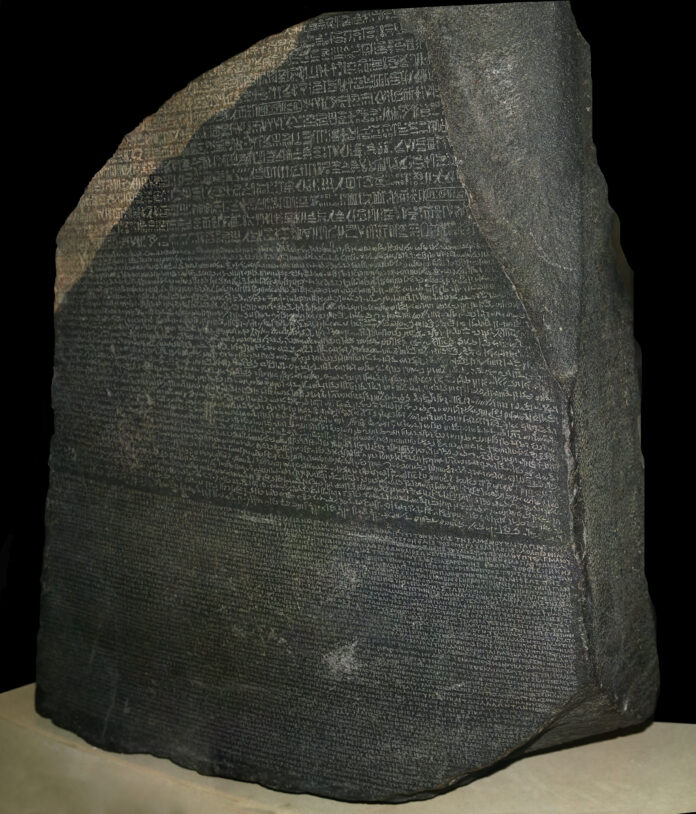

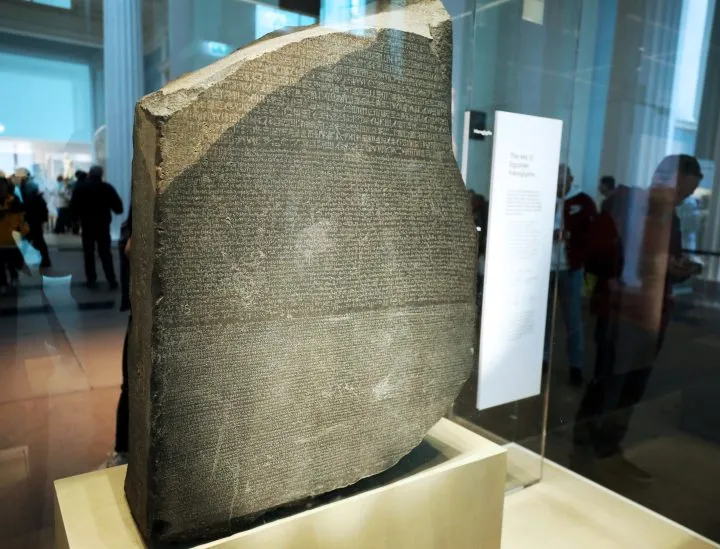

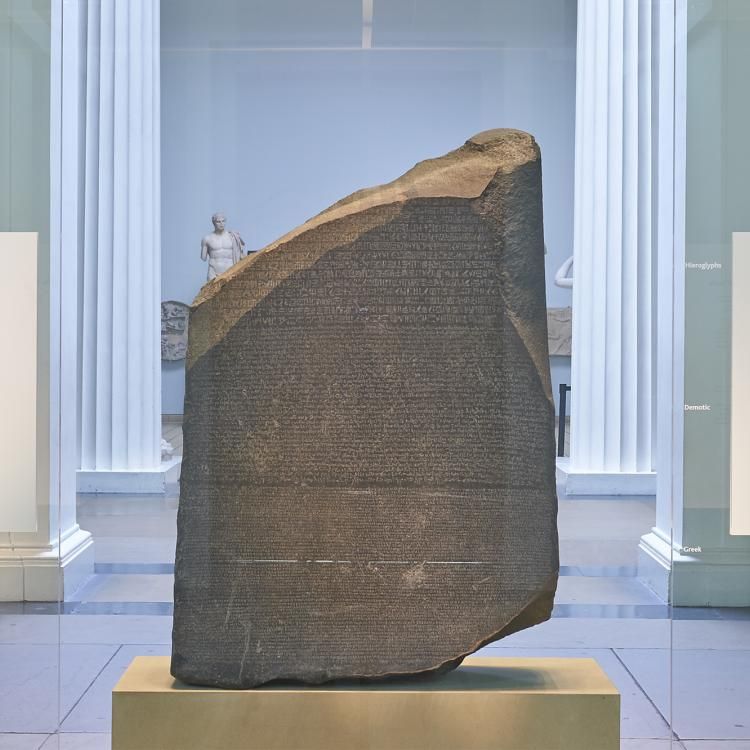

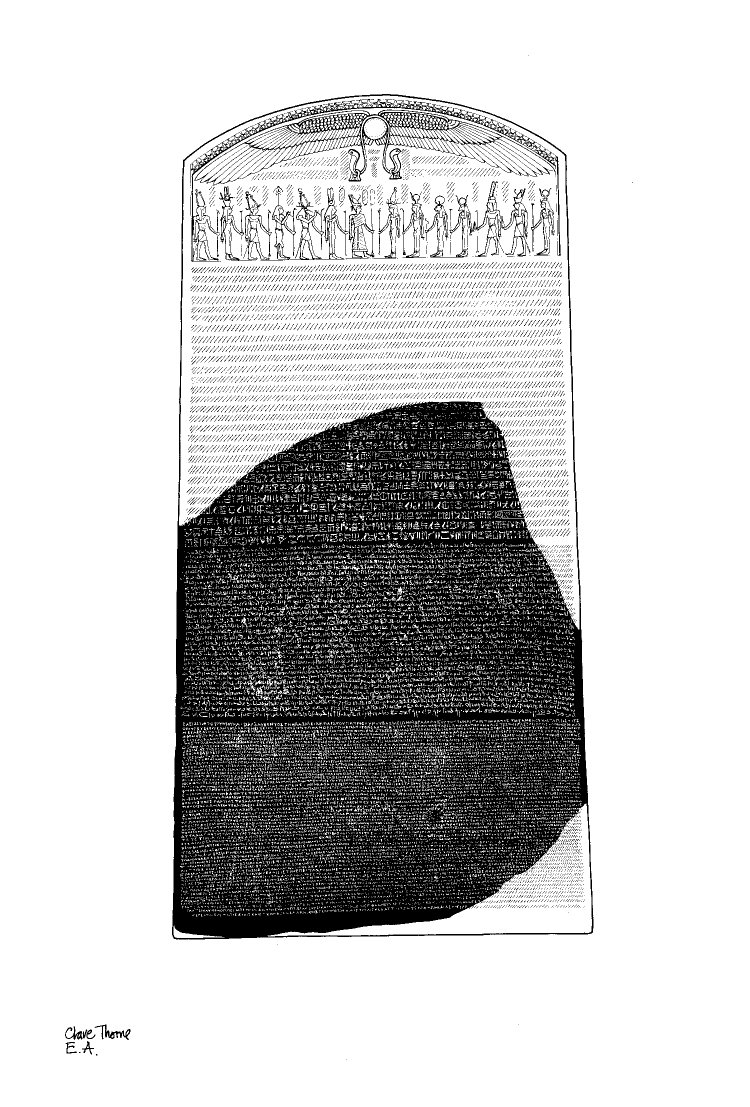

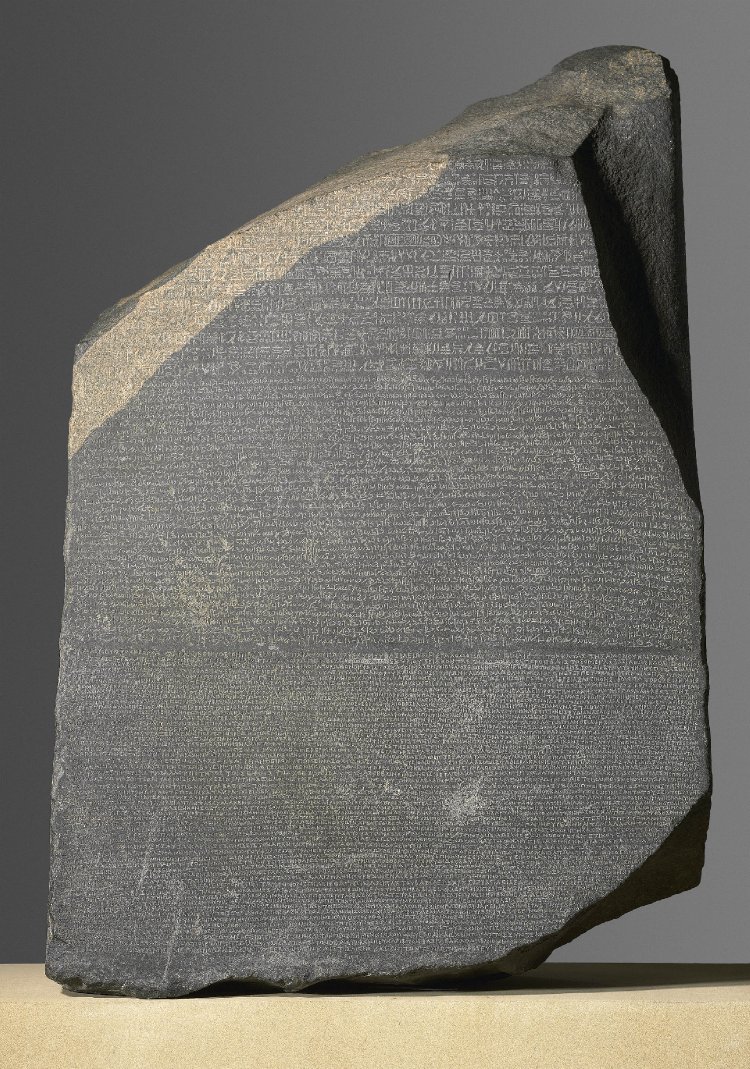

The Rosetta Stone was discovered in July 1799 in the city of Rosetta (now el Rashid) by French soldiers during Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt. It is a dark-colored stone slab inscribed with the same text in three scripts – Demotic, hieroglyphic, and Greek. This discovery was made during the construction of defensive works by the army, and the large stone slab was found by officer Pierre François Xavier Bouchard (1772–1832). He immediately recognized the significance of the parallel Greek and hieroglyphic texts, accurately predicting that each version represented a translation of the same text. This correct guess was confirmed when the Greek translation of the inscription was published: “The decree will be inscribed on a hard stone tablet in sacred characters (hieroglyphic), in native script (Demotic), and Greek language.”

Thus, the Rosetta Stone (French: “Pierre de Rosette”) is named after the city where it was found. Since its excavation, the Rosetta Stone has become an international icon, carrying various meanings to communities worldwide over the past two centuries. The stone now housed in the British Museum is a legacy of the colonial ambitions of France and Britain in their struggle to establish, maintain, and expand colonial empires at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries. The historical context is essential for understanding how different communities have constructed meanings around the Rosetta Stone.

For the Napoleon soldiers who discovered the stone, as well as for the British soldiers who seized it after France’s defeat, the stone represented political domination and scientific discovery. To many Egyptian communities, the stone has been seen as a symbol of cultural heritage and national identity. Some argue that the “export” of the Rosetta Stone was a “theft” of the colonial era that should be compensated by returning it to modern Egypt. Its crucial role in deciphering ancient Egyptian scripts led to the widespread use of the term “Rosetta Stone” as a general reference for anything that deciphers or reveals hidden secrets. The business community quickly capitalized on this popularity, as evidenced by applying this nickname to a successful language-learning software. The “Rosetta Stone” has become so prevalent in global culture in the 21st century that future generations may use the phrase without fully understanding its origin in the accidental discovery of a notable stone slab in Egypt.

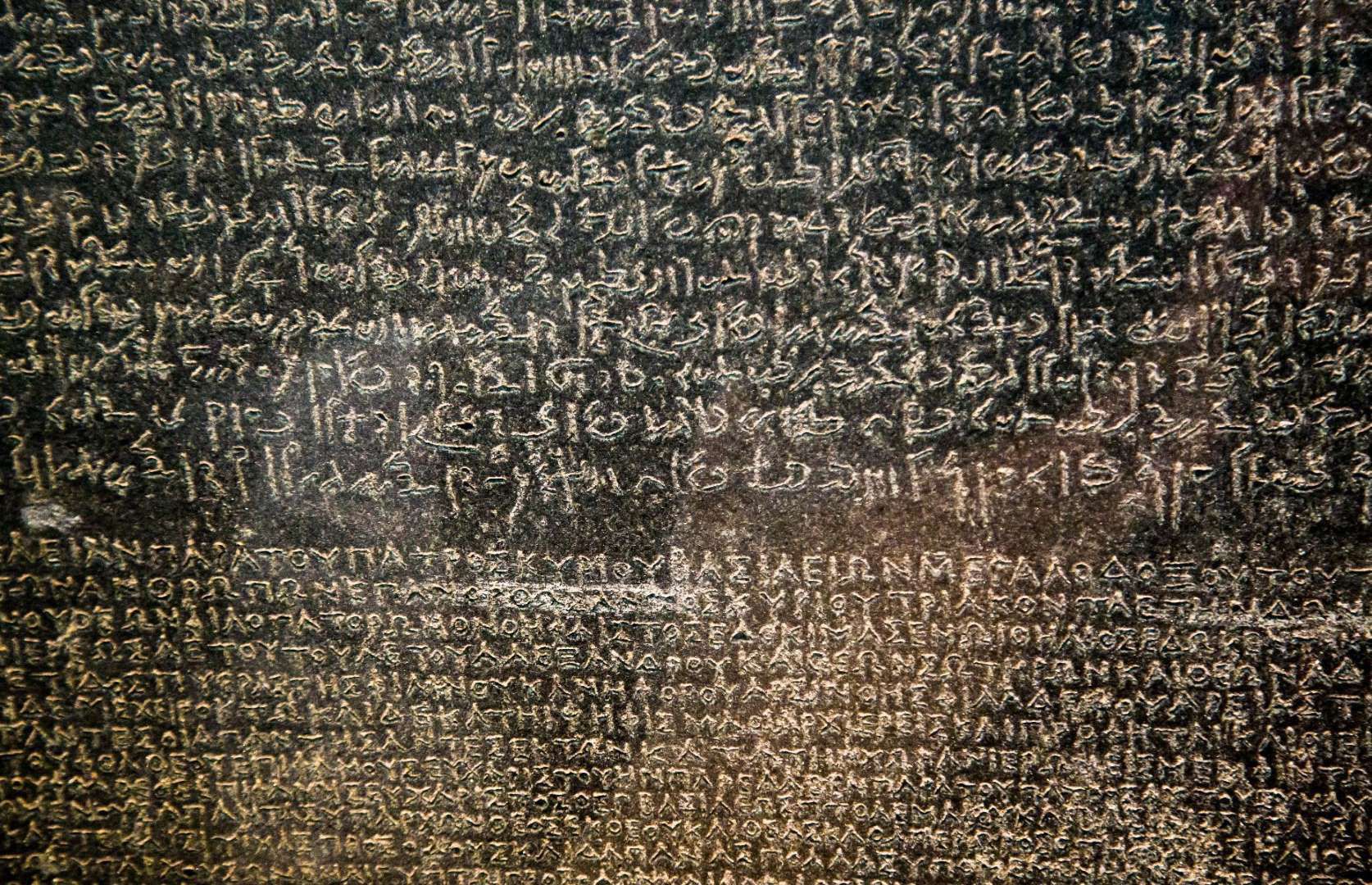

As scholars began serious efforts to decipher Egyptian scripts with the help of the Greek translation, the tri-lingual nature of the Rosetta Stone sparked a renaissance in decipherment in Europe. Although the popular imagination most closely associates the Rosetta Stone with Egyptian hieroglyphic writing, the earliest significant breakthroughs in decipherment focused on the Demotic script because it was better preserved among Egyptian versions. Antoine Isaac Silvestre de Sacy (1758–1838), a French linguist, and his Swedish pupil, Johan David Åkerblad (1763–1819), succeeded in identifying phonetic values for many signs called “alphabets,” reading personal names, and identifying translations for other words. The starting point for these efforts was using personal names of kings and queens mentioned in the Greek text and attempting to match their sounds to characters in the Egyptian versions.

These advances paved the way for the famous decipherment race between Thomas Young (1773–1829) and Jean-François Champollion (1790–1832) in deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphic writing. Both were highly accomplished. Young, who was 17 years older than Champollion, made remarkable progress in both hieroglyphic and Demotic scripts, but Champollion led in the final breakthrough. Champollion had devoted his intellectual efforts from childhood to ancient Egypt and studied the Coptic language under the guidance of Silvestre de Sacy. These efforts paid off when Champollion confirmed the hypothesis that Egyptian hieroglyphic writing indicated phonetic sounds, using his knowledge of Coptic to accurately deduce the pronunciation of hieroglyphic writing from the word “born” (ms, Coptic ⲙⲓⲥⲉ). At this point, he became the first person in over a millennium to read the inscriptions of Ramses and Thutmosis in their original language. According to legend, as recounted by Champollion’s nephew, upon realizing the significance of this confirmation, Champollion burst into tears in his brother’s office, shouting “I have found it!” and fainted, unconscious for nearly a week. With this outstanding achievement, Champollion established himself as the “father” of Egyptology, linking the Rosetta Stone to the birth of a new field of study.

With the mysteries of Egyptian texts deciphered by Champollion and his successors, scholars were able to confirm that the Rosetta Stone represented three translations of a single text. The content of that text, known from the Greek version, is a decree representing King Ptolemy V Epiphanes. On March 27, 196 BCE, a conference of priests from across Egypt met to commemorate the coronation of Ptolemy V Epiphanes the previous day in the city of Memphis, the traditional capital of Egypt. By this time, Memphis had economically lost its preeminence to Alexandria on the Mediterranean coast, but the city still retained symbolic importance as a link with Egypt’s pharaonic past. Royal decrees arising from this meeting were inscribed on stone slabs throughout the country. Because the meeting and coronation had taken place in Memphis, the text on the Rosetta Stone – and therefore sometimes the stone itself – is often referred to as the Memphis Decree. The inscription of the decree was found on other stone slabs from Elephantine and Tell el Yahudiya, while the inscriptions were compared with the Rosetta Stone from Nobaireh.

By the time the decree was written in 196 BCE, the king was only 13 years old, and a young monarch was enrolled in the difficulties of the Ptolemaic Dynasty. The rule of Ptolemy IV (221–204 BCE) ended with widespread riots across Egypt, including the establishment of a short-lived “native” dynasty in Upper Egypt after 206 BCE. Most of the decree is preserved on the Rosetta Stone in honor of Ptolemy V for ending the Delta part of this riot and the siege of Lycopolis City. The excavations of Tell Timai found traces of destruction and disruption during this time, which archaeologists have linked to Ptolemaic suppression of the rebellion. Although the boy king inherited the throne when his father died in 204 BCE, the child quickly received the prince’s hat from the guards in the palace, and the coronation was officially postponed for nine years until the child grew up; later ceremonies would be the cause of the Memphis Decree on the Rosetta Stone. Even though the resistance in the delta was defeated – according to the text on the Rosetta Stone – the rebellion of the Upper Egyptians continued until 186 BCE, when the royal sovereigns with the region was restored. The Decree itself is a complicated document proving the negotiation of power between two powerful groups: the Ptolemaic royal family and the Egyptian priest associations. In the text of the