Statue of the king as the guardian Ka, 18th dynasty, reign of Tutankhamen, 1336-1326 BCE, wood, gesso, black resin, gold leaf, bronze, white calcite and obsidian, 190 x 56 cm, Egyptian Museum.

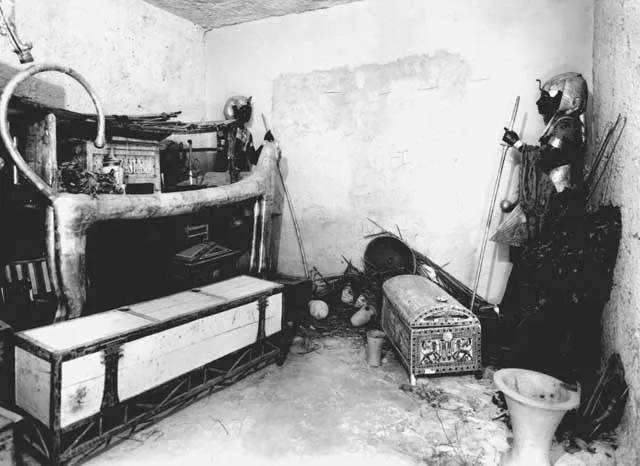

One day, at the exhibition “Tutankhamun: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh” at the Saatchi Gallery in London, a life-sized striding statue of King Tutankhamun caught everyone’s attention. This statue is one of a pair (the other remains in Cairo) and, in many ways, symbolizes our common misconceptions about Ancient Egypt and King Tutankhamun. With dramatic black and gold colors, these statues were said to be “life-size” because they represented the pharaoh at the same height as discoverer Howard Carter claimed after measuring the mummified body of the young king.

The Tutankhamun exhibition—which I was lucky enough to preview—emphasizes the priceless, luxurious, and unique nature of the king’s funerary treasures. In fact, from the broken remains of the contents of other tombs in the Valley of the Kings and elsewhere, it is clear that such statues were part of a standard set of funerary furniture that a king of Egypt’s New Kingdom could expect. Tutankhamun’s collection, if anything, was a pared-down version of this set.

The closest parallels to Tutankhamun’s statues come from the tomb of Ramesses I (KV 16). Giovanni Belzoni described their discovery in the burial chamber in 1817: “…in a corner, a statue standing erect, six feet six inches high, and beautifully cut out of sycamore wood: it is nearly perfect except the nose… in the chamber on our right hand, we found another statue like the first, but not perfect. No doubt they had once been placed one on each side of the sarcophagus, holding a lamp or some offering in their hands, one hand being stretched out in the proper posture for this, and the other hanging down.”

Two similar, though less well-preserved, statues come from the tomb of Horemheb (KV 57). Like those of Ramesses I, these are somewhat over life-size in scale. One other statue of this type originates from the tomb of Ramesses IX, now in the British Museum, and is roughly life-size. All of these are resin-coated and seem to have originally been gilded. The presence of this statue type throughout the Eighteenth Dynasty is indicated by fragments: in KV 20, the tomb of Hatshepsut/Thutmose I, excavators noted “a part of the face and foot of a large wooden statue covered with bitumen”; Amenhotep II was provided with a resin-coated example in the same pose as later statues but at only 80 cm in height, and fragments of sculpture on the same scale come from the tombs of Thutmose III and IV. Parts including “two left ears and two right feet” for “life-size wooden statues” were found in the cache tomb WV 25 but perhaps washed in from the neighboring tomb of Ay (WV 23). Taken together, this evidence suggests that such royal images increased in scale over time. Depictions of statues exactly similar to Tutankhamun’s appear in a scene of sculpture being produced in the tomb of the vizier Rekhmire (temp. Tuthmose III/Amenhotep II) – suggesting a consistent iconography over time.

In Tutankhamun’s pair, one wears the nemes headdress and the other a khat bag-wig. The same head coverings also occur on the pair of statues of Ramesses I, although other statues are insufficiently preserved to know if this pattern was standard. The khat-wearing statue of Tutankhamun has a text on the kilt apron labeling it as: “The Perfect God… royal Ka-spirit of (the) Horakhty, (the) Osiris… Nebkheperura, justified.” This favors the interpretation of the statue(s) as a home for the royal Ka-spirit.

The supposed function of these sculptures as “guardians” arises from the position at the doorway of the burial chamber of Tutankhamun’s (albeit truncated) tomb, the seemingly threatening maces they hold, and especially the over-life-size scale of the Horemheb and Ramesses I examples.

Carter initially coined the term “guardian statue,” and contemporary press accounts emphasized this apparently defensive function in descriptions; that is still how the statue is described in the Saatchi exhibition interpretation. However, in no simple way is the statue a “guardian.” The root of this persistent misinterpretation – absolutely typical for Egyptology – may lie in a deep-seated anxiety that the tomb was not supposed to be entered – the same apprehension that has fueled countless examples of mummy fiction.

One wonders if the statues actually represent a much more general freedom of movement and power for the deceased; spells from the Book of the Dead are illustrated by vignettes of the deceased holding a cane and scepter, and the same iconography notably occurs frequently on false doors from the Old Kingdom onwards. These images are not usually interpreted as “guardians” of the tomb – although they precisely parallel in two dimensions the “scene” set up in front of the door to Tutankhamun’s burial chamber in three dimensions.

As ever, Tutankhamun’s “treasures” say more about our modern anxieties about looking inside the tomb than they do about the ancient functions of objects such as sculptures.