Also known as the Catherine wheel or simply the wheel, the breaking wheel was a method of execution that crushed the limbs and bones of the condemned, sometimes over the course of several days. To this day, it stands as one of history’s most gruesome methods of execution. Mainly reserved for the worst criminals, its purpose was to inflict maximum pain and suffering, often in front of a large crowd.

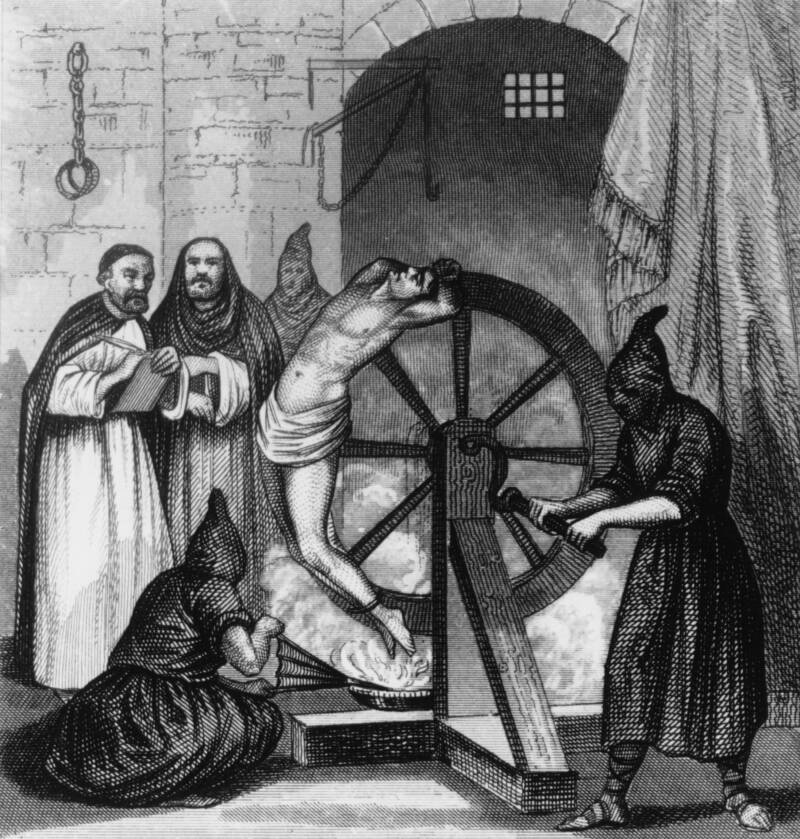

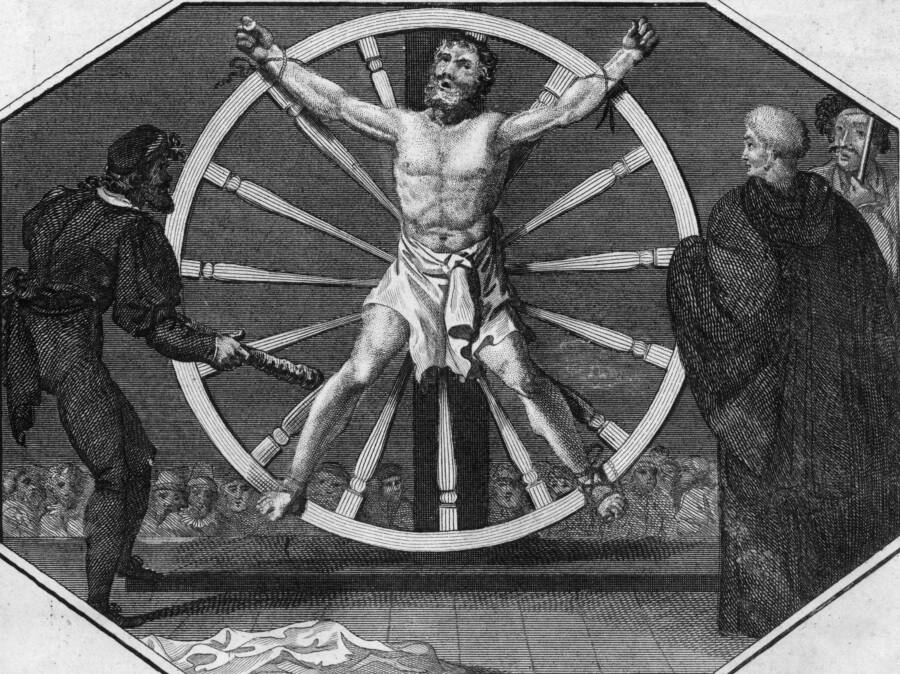

Those condemned to this punishment were either broken by the wheel or broken on the wheel. In the former, an executioner dropped a wheel on the victim to break their bones. In the latter, the victim was tied to a wheel, and the executioner systematically broke their bones with a cudgel.

Afterward, the victim would often be left on the wheel for hours or even days, their broken limbs gruesomely intertwined with the wheel’s spokes. Needless to say, it frequently took them a long time to die.

One of the most savage and cruel methods of execution ever devised, the breaking wheel eventually faded from use in the 19th century. However, its legacy of horror remains just as disturbing as ever.

The Breaking Wheel in Ancient Rome

The use of the wheel as a form of execution dates back to the Roman Empire, to the time of Emperor Commodus, son of Marcus Aurelius.

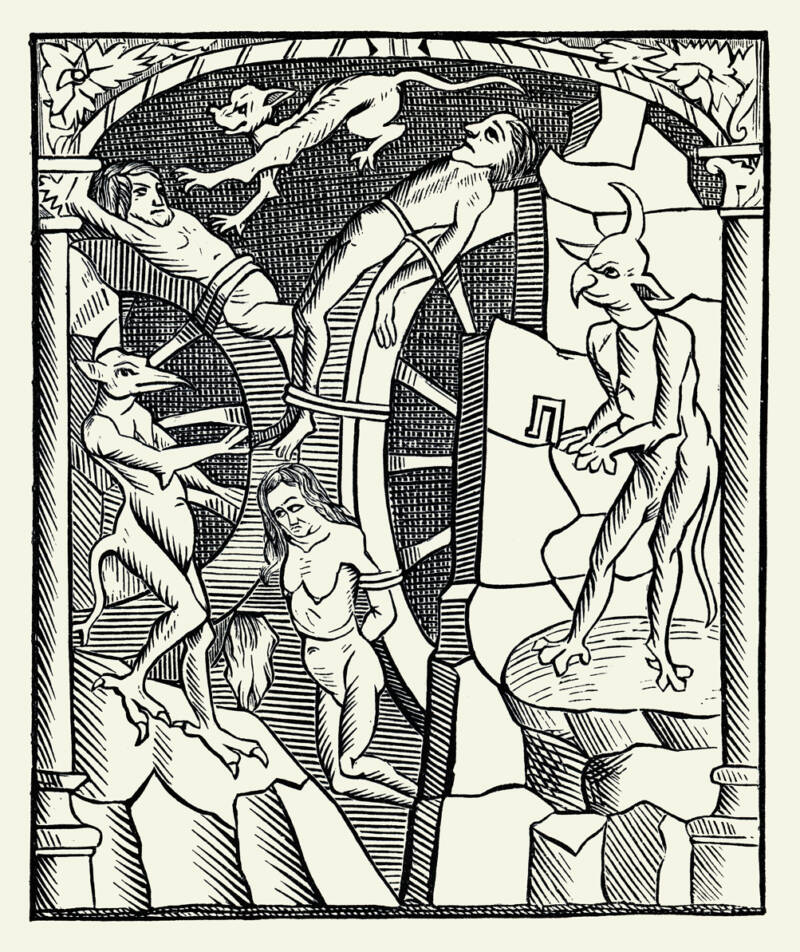

As Geoffrey Abbott writes in “What a Way to Go: The Guillotine, the Pendulum, the Thousand Cuts, the Spanish Donkey, and 66 Other Ways of Putting Someone to Death,” the Romans used the wheel as a tool to inflict pain. The executioner secured the condemned to a bench and placed an iron-flanged wheel on their body. They then used a hammer to smash the wheel into the victim, starting at their ankles and working their way up. The Romans typically used the wheel as a punishment for slaves and Christians — believing it would prevent resurrection — and soon devised new embellishments for the breaking wheel. As Abbott writes, victims were sometimes suspended vertically, facing the wheel, or bound to the wheel itself or around its circumference. In the latter case, executioners would sometimes light a fire beneath the wheel.

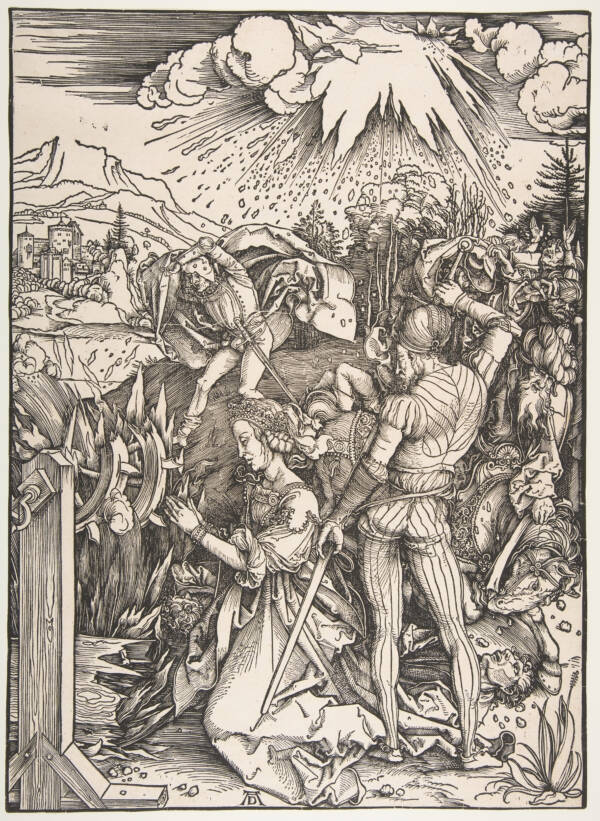

The first-century Roman-Jewish historian, Titus Flavius Josephus, described one such execution by the wheel, writing: “They fixed [the prisoner] about a great Wheel, whereof the noble-hearted youth had all his joints dislocated and all his limbs broken…the whole Wheel was stained with his blood.” One of the most infamous moments in the history of the breaking wheel occurred in the fourth century C.E. when the Romans attempted to use the torture device on St. Catherine of Alexandria. A Christian who refused to renounce her faith, Catherine was affixed to the wheel by her executioners. But then the breaking wheel fell apart.

Enraged by this apparent act of divine intervention, Emperor Maxentius ordered Catherine to be beheaded — at which point milk, not blood, allegedly flowed out of her body. Afterward, the breaking wheel came to be sometimes known as the wheel of Catherine. Over time, the use of the breaking wheel continued, no longer reserved for slaves or Christians, but used as punishment for crimes ranging from treason to murder.

Breaking Wheel Torture During the Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages, scores of people across Europe — and parts of Asia — were condemned to die by the breaking wheel. In 15th-century Zurich, for example, there was a methodology in place using the breaking wheel. According to the History Collection, victims were laid facedown on a board with the wheel placed on their backs. They were struck a total of nine times — twice in each arm and leg, and once in the spine.

Next, their broken bodies were woven through the wheel’s spokes, often while the victim was still alive. The wheel was then attached to a pole and driven into the ground, displaying the dying victim to all who passed.

Meanwhile, in France, executioners often rotated the wheel while the prisoners were affixed to the outer perimeter and struck them with a cudgel as they went around. The number of blows they received was determined by the court on a case-by-case basis, with minor offenses resulting in one or two blows before being killed. The final, fatal blow to the neck or chest came to be known as the coups de grâce, the blow of mercy.

For others, though, mercy was not swift.

In 1581, a German serial killer named Peter Niers was found guilty of 544 murders and sentenced to be broken by the wheel. To ensure that his punishment was severe, the executioners started with his ankles and slowly worked their way up to cause the utmost amount of pain. Niers received a total of 42 blows over the course of two days before being quartered alive.

Other prisoners were often simply left on the wheel after receiving their designated number of strikes. Rarely did they live longer than three days, often dying of shock, dehydration, or an attack from an animal.

And though it seems archaic and even primitive, the breaking wheel actually had a long run as far as execution methods go. In fact, it was used up until the 19th century.

The Wheel’s Final Years in Use

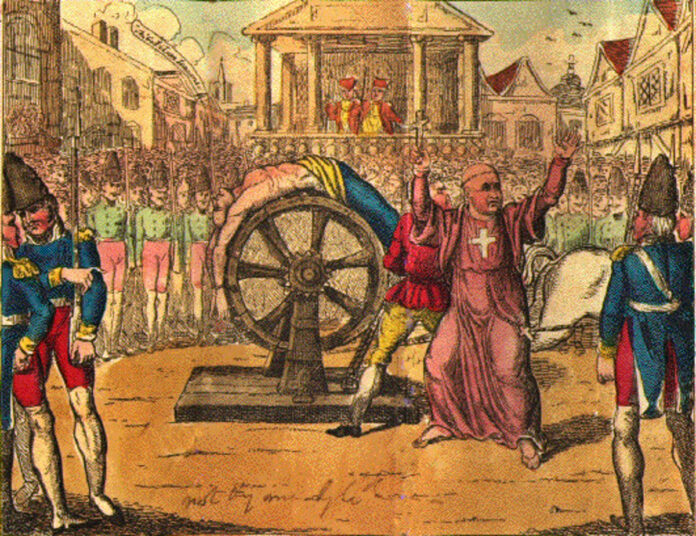

In places like France, the breaking wheel continued to be used as a method of execution long after the end of the Middle Ages. One of the most infamous uses of the breaking wheel took place in 1720 when Count Antoine de Horn and his companion, the Chevalier de Milhe, were accused of murdering a man in a tavern in Paris.

The two men had made an appointment with their victim, a share dealer, under the guise of selling him shares worth 100,000 crowns. But they actually sought to rob him. When a servant walked in and caught them in the act, they fled, only to be captured and sentenced to death.

Their sentencing caused quite an outrage, however, as numerous earls, dukes, bishops, and ladies pleaded to spare de Horn from his execution.

The pleas fell on deaf ears. Both the Count de Horn and the Chevalier de Milhe were tortured for information, then led to the breaking wheel. While Count de Horn was killed quickly, de Milhe was tortured for a long time before his executioner delivered the final blow. The last use of the breaking wheel in France took place in 1788, but it continued elsewhere in Europe and parts of South America well into the 19th century. Today, it’s happily fallen out of fashion.

But for hundreds of years, the breaking wheel stood as one of the most grisly execution methods imaginable. Most weren’t lucky enough to have it fall apart beneath them, as Catherine of Alexandria was. Instead, they suffered broken bones — and prayed for the coup de grâce.